Buyer’s guide: What to look for in a Mercedes SL R107 for sale

Mercedes-Benz W107 Buyer's Guide

Chapters

- Data Plate Decoder

- Buying guide

- General Considerations

- What to check first

- Body

- Engine and drivetrain

- Chassis

- Interior

- Production figures

Data Plate Decoder

Since it takes me a little while to manually check all the data from the many lists that are posted online, and I do check quite a lot of Mercedes, I spent some time building this data plate decoder. This saves me tons of time and it's way quicker than doing it manually.

I decided to make it public so you can use it freely and avoid getting bored to death while trying to decode the plate. Happy hunting!

How to use the decoder - quick guide

Quick guide

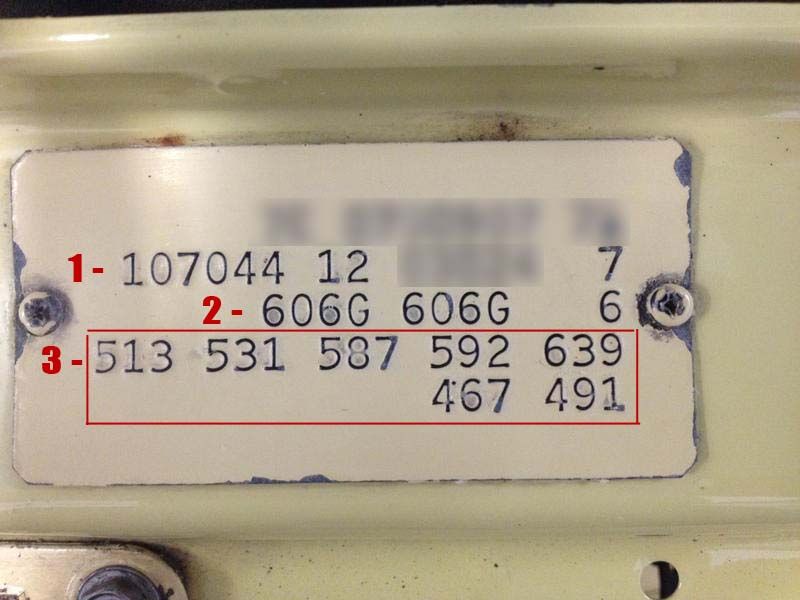

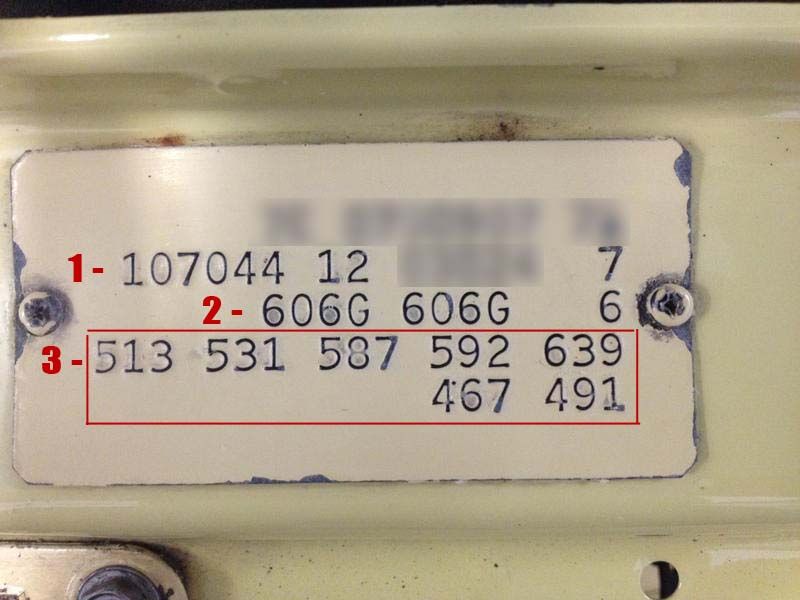

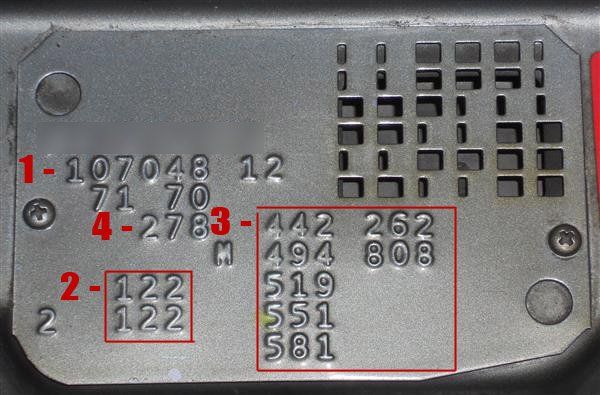

The data plate evolved through the years. Here's a quick guide to be sure you put the correct numbers in place.

Credit (originals): benzworld.org

- Model code (baumuster) / Steering and transmission code / Serial number (if any)

- Paint codes

- Option codes

- Interior code

Data Plate Information

Model, steering and transmission:

- Model code (baumuster): e.g. 107041

- Steering and transmission code: e.g. 12

- Serial number (if any): e.g. 28562

Interior codes (if any): e.g. 278

Paint codes: Just put the number code down here. "G" means that the paint supplier was Glasurit, while "H" was Herberts. Post-'85 models might show an "M" for metallic paint, "F" for standard or "C" for clear coat.

- Paint code 1 (body): e.g. 050

- Paint code 2 (hardtop): e.g. 050

Option codes: The option codes stamped in this plate only refers to those that affect the building process. You can check the data card of your 107 to check for more options.

I'm a bit obsessive when I check cars. I try to get as many information as I can to better assess its history, value and state. Whenever I check a R107, C107 or even W113 Pagoda for sale, one of the first steps I take is to decode the data plate and see the original equipment and model.

From there, I can do a quick first run to see it this could be a matching numbers car (fully confirmed by a MB Data Card check afterwards) and if it keeps all the original options and nothing weird is going on. Then, I can take my time and do a more thorough inspection.

Buying guide

It is easy to get lost in the daunting sea of model years, engines, country-specific specs, and general troubleshooting when we talk about the Mercedes-Benz W107.

So I wrote a quick guide for everyone to use when they go see a Mercedes-Benz W107 for sale and don't want to spend hours learning about the car. I get it, driving feels better than spending lots of hours learning about the W107.

Actually, I find that thrilling and very fun to deal with. But I'm just a weirdo and many people hate that process, which I completely understand.

Heck, even the denomination can get a bit confusing. Officially, the 1971-1989 Mercedes-Benz SL/C has never been coded W107 (W is for Wagen) like its sedan counterparts or even past SLs (W113 Pagoda or W198 I/II 300SL). But the MB community have adopted the W107 to simplify things.

The official codes were R107 for the SL (R is for Roadster) and C107 for the SLC (C is for Coupe). Ever since then, the Roadsters made by Mercedes have been given the "R" code.

The W113 SL Pagoda was on production during 8 years, and not that many were sold, making it hard to find a good unit.

Fortunately, the W107 has been in production for many years, 18 for the R107 SL. So, being made in such large quantities, we can expect to see a lot of neglected cars and, hopefully, a lot of great cars.

That opens up the possibility of walking away from a car that doesn't fully satisfies our expectations, whichever they would be.

Though the building quality of the R107 and C107 is quite sturdy (hence the 18 year life span), it does have some weak spots and general aspects to bear in mind, just like any classic car.

General considerations

This can be applied to many classic cars for sale out there, and the W107 is no exception here. But, for starters, it is good to remember them so we don't fall victims of the car's allure:

Low mileage cars might not be that pretty

Sure, we all want a mint condition, low-mileage unit. But, has it been serviced regularly and used sparingly during all these years?

Like our knees and elbows, the hoses, gaskets, seals and rubber/plastic parts need movement to grease themselves.

So, that 40.000 km SL that's been sitting on a parking spot for the last 20 years unmolested will need a good service bill before hitting the road again.

Do not shy away from a well serviced, high mileage W107. They handle mileage like a champ.

Service history is KING

A good service record proves two highly important things:

- The car's been serviced when it should have been

- The owner(s) are likely to have been careful with the car

Plus, having the service records is a vital part when it comes to document the history of the car, which, at least for me and a good part of the classic car community, matters as much as the car itself.

First series versus second series

This is completely subjective. I love the looks of the first series with nice Bundt wheels. But I tend to love any first series of any given car, so this is just a pure matter of taste.

The W107 second series cars are generally more sought-after cars because they are really more refined and essentially revamped cars. They have several key issues resolved or mitigated and their road holding was substantially improved, so people consider it's kind of a no-brainer, easier car to buy since it isn't that prone to failures.

The W107 first series may not be that refined and deal with more issues, but that doesn't mean that they are superb cars and can be as reliable as a second series. We just have to keep in mind to look a bit deeper.

With that out of the way, we begin to delve into the particularities of the W107.

What to inspect in a Mercedes-Benz R107 for sale

The 'triad from hell'

There's quite a lot to check in the car if we want to be thorough, but there are 3 aspects that we MUST check before inspecting the car further:

- Corrosion and rust: the nemesis of any classic car enthusiast

- Sub-frame cracking: a well-known issue in V8 SL/Cs

- Timing chain rattle: a ticking bomb under the hood

I'll expand on each point below, but let me be clear here: failure to pass any of these 3 points means that you put on a big smile on your face, thank the owner for his time, get back to your car and drive home as fast as you can. No matter how well everything else is.

What? The car looks smoking hot and you don't mind repairing it since the price is low? Ok then, go ahead. Don't come knocking when you spend 2-3x the amount you paid for the car in bills.

Those kind of cars are what nightmares are made of. Restoration is an option when the value of a top notch car is so high that you can risk undergoing a restoration.

The W107 are not in that ballpark, not by any chance. And it doesn't seem that it's going to be anywhere soon given the huge production numbers.

The general rule of thumb is to buy the best you can afford, given that the car is in good overall condition and doesn't have those three problems.

Body

Corrosion

Most classic cars rust. The W107 is no exception to this rule. And it is both expensive and time consuming to repair.

Though Mercedes build high-quality cars, they do not escape metal corrosion. Up to 1976, the steel used in production in all Mercedes range tended to rust rather quickly. I cannot tell you how many rusted Pagodas I've seen throughout the years, even those well preserved.

The steel quality improved in 1976 and in 1980 cavity wax injection was made standard on the production line.

Later on 1986, they galvanized fenders, doors and several other body parts and added wheel arch liners that greatly improved the rust issue.

Here's a list of hotspots of corrosion to look for:

- Body sills

- Headlights

- Hood

- Floors on the passenger compartment

- Doors

- Trunk

- Lower side skirts

- Wheel arches, especially rear arches

- Front subframe

- Suspension wishbones

- Bulkhead on both sides

- Chrome mouldings around the car

- Bumpers

- Sunroof (if present)

Passenger compartment

Check for rubber seals all round. With the youngest SL approaching its 30 years old, it is very likely that those seals let some water in.

Check for any sign of water inside the cabin. Dampness, stream marks or tiny specks of corrosion indicate a nearby leaking area.

The front windshield was glued inside the bulkhead to achieve the rigidity requested by USA legislation to allow an open top car without the Targa.

It is worth checking if this sealant is worn out and could be leaking inside the car too.

Look for leaks in the tricky vacuum operated central locking system. When in order, both doors should lock quick and at the same time. Otherwise, you might be in for a proper overhaul of the system.

Trunk

The same trouble that plagued Pagodas for years can be found in the W107s, but not to the same degree: water in the trunk.

Check carefully for corrosion spots or parts of degraded rubber. Water usually finds its way into the trunk via old rubber seals that don't seal that well anymore.

It is advisable to replace the rubber seals around this area if they have never been, even if the trunk is completely dry.

Bumpers

Check for any dents or twists. Also, corrosion must be carefully checked.

Due to its shape, corrosion might not be so easy to spot, since they can rot from the inside out (especially the rear bumper).

Try to clean the inside of the bumper with a rag to see if there's any corrosion, not only common dirt.

Sunroof on SLCs

As most sunroofs on any classic car, water is their nemesis.

Debris blocks any drainage pipes and deteriorates the area, leading to corrosion and water leaks.

The wiring can also be faulty sometimes due to installation/wiring hobgoblins.

Soft top

As any roadster owner will know, long periods of time without putting the soft top on the car results in a noticeable shrinkage of the soft top itself.

This can be puzzling, especially for those soft tops that look mint. This means that is has been kept in storage for long or the car just ran with the hardtop on.

In that case, check that the soft top latches perfectly on to the front mounts and that the mechanism is not blocked.

If the soft top has been regularly used, check for proper adjustment all around, smooth folding and unfolding, good clear windows and any signs of leakage. Any rip, tiny holes or weird discoloration in particular places might need a costly repair.

Hardtop

The key thing here is to check if it latches on/releases from the body rather easily. Any trouble here usually relates to slacking latches or broken/trapped cables.

Also, check for any missing chrome parts that might have come off after neglected storage or clumsy attempts to put the hardtop on.

Engine and drivetrain

One rule when inspecting cars is to check the engine completely cold. When the car is cold, all the weird noises and possible faults have nowhere to hide. So, always try to check the engine cold.

Oil pressure

The values you should look for: ~3 bar on startup/cold engine, ~0.5/0.8 bar at operating temperature.

It also has to go up in pressure anytime you hit the throttle and the revs pick up.

Oil leaks

Let's face it; most classic cars have leaky engines. Mostly due to poor tolerances on fabrication, and the years of wear and tear don't help the tiniest bit.

In general, it shouldn't be something to worry about. But you should watch carefully if there's any big one or if the oil leak falls directly into the exhaust header, which can sometimes be the case in the V8s.

Cooling

We're talking about big engines in the SL/C range, and boy they do give off a lot of heat.

Fortunately, the cooling system of the W107 is superb and deals with the engine perfectly. Take the car for a drive and check the coolant temperature all along.

If you see the engine overheating in open roads without pushing it, either the car is low on coolant or the radiator is clogged.

Fuel injection

The Bosch systems are reliable, but we're talking about 30+ years old fuel injection systems, so it can get faulty sometimes.

If, when you test drive the car, you find the car struggles to start (both on cold or hot), runs poor or shakes when you step on the gas, it's probably related to the fuel injection.

It can be adjusted but if the car is in shambles it can be quite costly to replace.

Timing chain

Chains are used to drive the valvetrain synchronized with the crankshaft so it runs properly.

Since chains are way more durable than belts, the time between services can be stretched to 160-200k miles (250-320k kilometers) if properly maintained. The SL engines are pretty much bulletproof if they've been well kept.

However, the W107 has seen its value plummet since new for years, and tons of units have been neglected by second-third-n owners that didn't have the purchasing power of the first owner, and won't be as likely to keep the car properly serviced.

And thus, the timing chain lifespan shortens dramatically, making it a ticking bomb for the soon-to-be owner. Bad-to-no maintenance can bring down the chain life to only 100-120k kilometers (about 80k miles).

We must approach inspection in this point in two ways

First, with the engine cold, start the car and look for a rattling noise that stays there for 15-20 seconds and then quiets down.

Does it sound? The chain is stretched and needs to be replaced or the chain tensioner is gone and needs replacement.

Otherwise, it can become a bit naughty and skip a tooth, two or more on the camshaft sprocket. And then the pistons get angry with the valves, bend them and that's it. Engine blown. See ya.

The second thing we must check if there's no such sound coming from the engine is a bit trickier.

All the distribution parts surrounding the timing chain have their function, such as rails, tensioner and guides. They are coated with plastic to avoid friction and allow a smoother ride.

Disregarding the mileage, the years make the plastic brittle and prone to lose tiny bits here and there. If one bit falls into the chain and makes it jump the timing, game over, as we've already exposed before.

This can happen with very low mileage but not well maintained cars. If the car has a good service record as per the MB guidelines, it should have that parts replaced.

Check carefully if there's evidence for this. Otherwise, consider this as a cost to add to the purchasing price when negotiating with the seller.

The single-chain issue

Nearly all V8 mounted on SLs and SLCs have a double-row timing chain to avoid premature stretching since the V shape of the engine demands a fairly long chain.

This proved to be bulletproof if we didn't get lazy with the maintenance.

However, from 1981 to 1983, the 380SL version that was exported to USA was equipped with a 3.8 liter V8 that only had a single-row chain instead of the double-chain of the European version.

Bad idea. Broken chains and weird engine disasters followed even to properly maintained cars. Mercedes-Benz called 380SL owners of that period to the workshop to replace the chains to a double-row chain at no cost.

If you come across a 380SL of that production range, check that it had the chain conversion, either physically or in the service history if available.

The 300SL also has a single row chain, but since the chain is way shorter it didn't wreak havoc. The same considerations for the V8 must be considered, keeping an eye on the rubber parts at 70-100k kilometers.

Hydraulic lifters

This part keeps the proper clearance between rocker arms and the camshaft. If the car has not been properly maintained, the valvetrain in general wears out prematurely.

The lifters make a pretty recognizable clicking sound on the upper part of the engine due to increased clearance.

This is not usually a big deal, but it's a heads up to look for further maintenance defects.

Transmission

Both manual and automatic transmissions are sturdy. A careful check and/or overhaul must be done at 150.000 kilometers (~100.000 miles).

Chassis

Subframe

The front subframe in early cars is prone to cracking. Yes, cracking. The construction wasn't as sturdy as it should be, and the stress provoked by road handling, bumps and potholes makes the V8 cars prone to cracks.

Not only this, the most frequent part where the crack starts is near the front control arm attachment to the subframe.

This means loose steering, weird handling and, worst case scenario, an accident.

Despite MB addressed the issue for the 350SL and 450SL and replaced those subframes, there's evidence for cracks on other 280SL and other V8.

The best way to address this is to have it inspected by a Mercedes dealer and do the due diligence on the VIN.

Suspension

The main concern here is pure wear. Though the W107 is not by any means a "hard" car suspension-wise, it doesn't mean that the car should dive the nose deep at the slightest touch on the brakes, nor should it rebound like mad if you drive over a bump.

Check for worn shock absorbers, worn out bushings and excessive play in the control arms and ball joints.

A common modification was to replace wheels for a wider set to give a more aggressive look or the infamous "more grip". If you spot this, check carefully the suspension because these mods change the geometry on the suspension and increase the stress.

Steering

Another key point to check is for the accuracy of the steering. While driving, pay attention to how the car steers.

Check if you can point the car with precision and at once. If the car is acting a bit weird or it doesn't steer consistently each time, the steering box might be worn out.

Brakes

No special thing to bear in mind rather than the usual check.

The W107 is a heavy car but brakes perfectly with its brake discs all-round. Check for brake pad thickness; any screeching might indicate that they need replacement. A spongy feeling on the brake pedal means there's air in the brake lines, so it needs bleeding and a leak check.

If the car has been parked for a long time, it might have one of the calipers seized. While you test drive it on an open road, try to brake firmly (without jumping on them like a mad man!) and see if the car keeps straight. If the car turns while braking, one of the calipers is seized and needs an overhaul.

Interior

Seats

A nice, well maintained interior is of course the best of the options here.

Leather or MB Tex were once the most desired options, but now, 30 years after the last W107 left the factory, the fabric seats are particularly sought-after due to its rarity and lower chance to find them in good condition. Bonus points for the checkered cloth.

Check for wear and tear all around, including the lower part of the seats which is not as visible and tends to be forgotten when doing a cosmetic makeover.

Air conditioning

Don't expect a 2016 S-Class air conditioning here. Does it cool? Yes. Does it cool A LOT? No sir.

That said, it is critical to check if it works. The system in the W107 is quite tricky and depending on the piece needed to replace you'd have to remove half the interior! So, better check it out.

Special mention to the 450SL/C from 1977 to 1980 and the 380SL on 1981, both of which mounted a Chrysler servo unit that is famous for its willingness to stop working.

Check that it really blows air, which means that both the servo and the blowers are working. Failure to do so might mean that one or both parts need to be taken care of.

Also check that the pods and vents aren't acting weird, especially in late models.

Production figures of the SL R107 and the SLC C107

Mercedes-Benz SL (R107) - European market - First series (November 1970 – October 1985)

| Model | Model code (Baumuster) | Engine | Power | Production starts in | Production ends in | Production numbers (all markets) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 280 SL | 107.042 | 2746cc - L6 | 182 HP | 05/1974 | 08/1985 | 25436 |

| 350 SL | 107.043 | 3499cc - V8 | 200 HP | 11/1970 | 03/1980 | 15304 |

| 450 SL | 107.044 | 4520cc - V8 | 222 HP | 02/1973 | 03/1980 | 66298 |

| 380 SL | 107.045 | 3818cc - V8 | 215 HP | 02/1980 | 10/1985 | 53200 |

| 500 SL | 107.046 | 4973cc - V8 | 240 HP | 04/1980 | 09/1985 | 11812 |

Mercedes-Benz SL (R107) – North American Market (March 1971 – August 1989)

| Model | Model code (Baumuster) | Engine | Power | Production starts in | Production ends in | Production numbers (all markets) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 450 SL | 107.044 | 4520cc - V8 | 180 HP | 03/1971 | 03/1980 | 66298 |

| 380 SL | 107.045 | 3818cc - V8 | 155 HP | 02/1980 | 10/1985 | 53200 |

| 560 SL | 107.048 | 5549cc - V8 | 227 HP | 06/1985 | 08/1989 | 49347 |

Mercedes-Benz SL (R107) - European market - Second series (May 1985 – August 1989)

| Model | Model code (Baumuster) | Engine | Power | Production starts in | Production ends in | Production numbers (all markets) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300 SL | 107.041 | 2962cc - L6 | 185 HP | 05/1985 | 08/1989 | 13742 |

| 420 SL | 107.047 | 4196cc - V8 | 215 HP | 07/1985 | 08/1989 | 2148 |

| 500 SL | 107.046 | 4973cc - V8 | 240 HP | 09/1985 | 08/1989 | 11812 |

Mercedes-Benz SLC (C107) - European market (June 1971 – September 1981)

| Model | Model code (Baumuster) | Engine | Power | Production starts in | Production ends in | Production numbers (all markets) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 280 SLC | 107.022 | 2746cc - L6 | 182 HP | 05/1974 | 09/1981 | 10666 |

| 350 SLC | 107.023 | 3499cc - V8 | 200 HP | 06/1971 | 03/1980 | 13925 |

| 380 SLC | 107.025 | 3818cc - V8 | 215 HP | 02/1980 | 09/1981 | 3789 |

| 450 SLC | 107.024 | 4520cc - V8 | 222 HP | 02/1972 | 10/1980 | 31739 |

| 450 SLC 5.0 | 107.026 | 5025cc – V8 | 240 HP | 09/1977 | 03/1980 | 2769* same baumuster |

| 500 SLC | 107.026 | 4973cc - V8 | 240 HP | 03/1980 | 09/1981 |

Mercedes-Benz SLC (C107) - North american market (June 1971 – September 1981)

| Model | Model code (Baumuster) | Engine | Power | Production starts in | Production ends in | Production numbers (all markets) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 380 SLC | 107.025 | 3818cc - V8 | 155 HP | 02/1980 | 09/1981 | 3789 |

| 450 SLC | 107.024 | 4520cc - V8 | 180 HP | 02/1972 | 10/1980 | 31739 |